The subversive Santa Muerte, favored by undocumented migrants, including LGBTQ migrants, provides solace and protection against both church and state, while also reflecting their liminal, precarious lives. Finally, the essay returns to the central question of why both church and state oppose and feel threatened by Santa Muerte. The extended discussion about borders, whether between nation states, genders, or legal statuses, provides the context for understanding the ever-increasing popularity of Santa Muerte. This essay explores the US obsession with the southern border as a means of keeping the “body” of the state pure the role the Roman Catholic Church plays in caring for undocumented migrant bodies the legal and social limbo faced by unauthorized persons in the United States when they are no longer physically outside the border, but in the “outside of the inside” (Kuntsman 2009) and how borders and immigration policies control and reproduce gender and sexuality. Santa Muerte perfectly embodies opposition to contemporary US responses to undocumented migrants, as well as historic (and contemporary) church and state exclusion of LGBTQ migrants. Both church and state actively oppose an unofficial saint worshiped by millions in Mexico and in the United States. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mexico City claims that the Holy Death is in “direct opposition to the teachings of the Church and proper worship” (O’Connell 2009, n.p.). Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, head of the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Culture, declared, “It’s not religion just because it’s dressed up like religion it’s a blasphemy against religion” (quoted in Guillermoprieto 2013, n.p.). The Church in Mexico and the Vatican forbid her worship. The Roman Catholic Church also fears the skinny saint. Programs and writings concerning wellness and spirituality can provide ‘spiritual armor’” (Bunker 2013). A Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) law enforcement bulletin claims: “Santa Muerte informational training can prove so stressful for some law enforcement and public safety officers that they can become physically ill and pass out. The Drug Enforcement Agency, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, the Mexican government, and the Mexican military all actively oppose the worship of Santa Muerte. What surprised me, however, was that government entities both in the US and in Mexico, shared my interest in the Bony Lady. I came to understand her popularity among migrants and LGBTQ communities in Mexico she is associated with those living precarious lives and/or engaged in dangerous undertakings. Since early 2000, worship has grown dramatically in Mexico and in the US, especially among migrants. Now, the Bony Lady is “out” and very visible.

In the early years of my research, few people in Mexico would talk to me about her, and few in the US knew of her she was either underground or unknown. Thus began over a decade of following Santa Muerte to Mexico, California, the US/Mexico Border, and even small towns in northern Wisconsin. I had not encountered the saint before and was surprised by her obvious importance in their lives.

Santa Muerte featured prominently on home altars in their single-room occupancy hotel rooms.

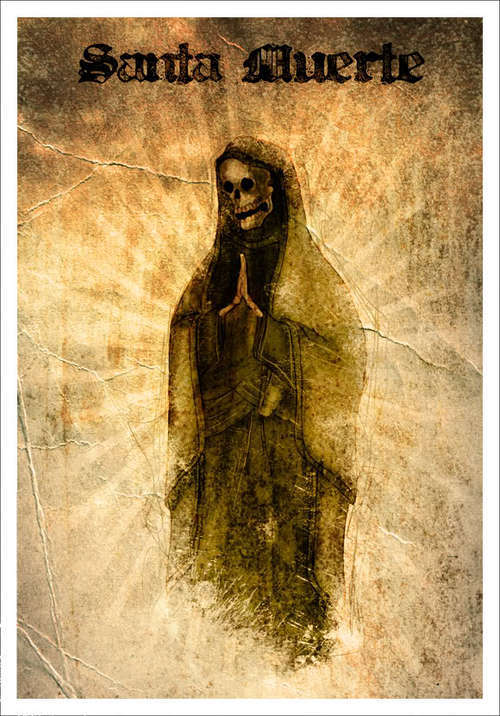

I first met Santa Muerte in 2002 during fieldwork with undocumented migrant transgender sex workers from Guadalajara, Mexico, who lived in San Francisco. Also known as La Flaquita (The Skinny One), La Niña Blanca (The White Girl), La Niña Negra (The Black Girl), Señora de las Sombras (Lady of the Shadows), La Huesuda (Bony Lady), La Niña Bonita (The Pretty Girl), La Madrina (The Godmother), and more reverently, La Santísima Muerte (The Most Holy Death), she is a beloved saint of dispossessed peoples. La Santa Muerte has crossed the US/Mexico Border for over a decade, accompanying her devotees on their arduous journeys north. Santa Muerte: Saint of the Dispossessed, Enemy of Church and State Lois Ann Lorentzen | University of San Francisco Santa Muerte, south of Nuevo Laredo, México.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)